by David Berkey

When I first heard about the Gradual Release of Responsibility, a.k.a. “GRR,” I wasn’t on snow, yet there was snow around us, albeit not much. This year, the fog and wind in November at Timberline forced us indoors, with groups all clamoring for space to be heard – Grrrrrrr! Fortunately, the group presentation by Linda Cowan was in the cafeteria, behind glass, and we could hear everything. Linda’s topic was GRR. What I discovered was a tool to potentially assist instructors, new and experienced alike, to become better instructors. It’s not complicated. Most instructors utilize some form of this model in one way or another. I’ve been experimenting with this model in my clinics and classes. All I can say is, “It works!”

After talking to others about Linda’s presentation, I found a lot of skepticism. On our drive back to Seattle, my fellow Training Directors (TDs) discussed if there were any merits to this system. I was in the “pro camp,” while another pointed out his doubts as to its value to the customer. He pointed out that if he pays for a clinic or lesson, he would prefer not hearing from his peer group. He would want input from the paid professional. That was a good point, but I pointed out that it’s up to the professional to guide the discussions, so all students could benefit from easily measured, specific actions. By each student participating, each better owned the information provided.

No sale. He thought that GRR would produce more Grrrrrrrrrrr, or frustration for the student. Still, I wanted to experiment. I needed to find out for myself. As it turned out, I demonstrated GRR’s usefulness in our Level I clinics. Read on and

you’ll see how.

First, what is GRR?

As I mentioned already this acronym stands for Gradual Release of Responsibility. It was developed, as I remember Linda’s story, by a swim coach. He found that by using GRR, he could offer more targeted, personalized instruction at a cognitive level, which provided for greater understanding by his swimmers. They actually helped or taught each other, with guided feedback from the coach, whereby he could constantly check for understanding, providing correction where necessary. This model is such a hot button in education that the Northshore School District located on the “east side” with its district office in Bothell, WA has adopted it. Being an educator in that district is why Linda is so familiar with the concept and a great resource, should you want to understand more. Fortunately, her home turf at Stevens Pass is my turf too, so we get her guidance more frequently, if needed.

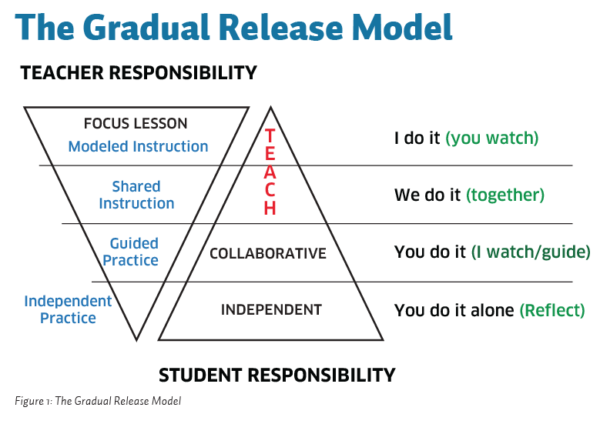

As you can see by the Figure aove, and which can be found on the PSIA-NW website, it illustrates that the teacher and student are in what we call a dance. The teacher takes the lead and shows, or

demonstrates, as in “I do it,” then he/she involves the students in a “we do it” together, as in student and teacher dancing together, to check for understanding and provide individual feedback. The instructor then gives the reigns to the students in a “you do it” (teacher watches/guides), with students dancing and guiding each other, increasing their level of understanding by them paying attention to specific desired movements or outcomes.

Finally, students move to a “you do it alone” mode, becoming independent, dancing by themselves. Students end up with better ownership of what was taught. As instructors, we set them free, as hopefully better skiers. But, do our clients truly have ownership of the knowledge we have imparted? I have found that by applying GRR, my students are more self-aware, with a better understanding of body movements and the cause and effect of those movements. They seem to value what they’re taught and want more lessons. They want to learn.

So how does it work?

I can best explain this by some examples. How else do teachers best explain their actions?

Example 1: Earlier this season, we started clinics for our Level 1 candidates. Some are quite young and one in particular was frustrating one of the TDs. He just wasn’t paying attention, standing still and listening. Remember the doubt expressed in the car when returning from Timberline? This was one of those TDs, and he was irritated with this candidate’s lack of attention. (Grrrrrrr!) I asked if I could try something. With his blessing, I paired everyone up, asking everyone to pay attention to their partner’s movements. The task we had demonstrated was an edged traverse. I again explained the points to look for, but asked them to only observe the outcome: to see if their partner’s tracks were evenly spaced, both being parallel and if the tracks showed signs of slipping or edged skis. I asked them to work with each other, then asked them to comment on what they observed in front of the group. OMG! They had to pay attention.

In addition, both of us TDs could check their individual levels of understanding and keep them from not straying from the defined outcome. Rather than correct overall skiing, I wanted them to concentrate only on those body movements that affected the creation of the desired tracks in the snow. As we were also working on body alignment and balance and how it affects good skiing, we could guide them toward the cause and effect of correct body alignment to a traverse. After half a run working with the pairs, I asked them to take on a bit more responsibility and work on each other to a meeting point down the hill, trying to perfect each other’s tracks. At this point, both of us TDs were to back off and observe what they did, only stepping in when there was a question or obvious lack of understanding. Sometimes, we had to remind them of the goal: 2 parallel, edged tracks across the snow while in a balanced, correct stance. In the end, we did some free skiing, keeping to the theme of stance and balance. As for input from us TDs, we kept it to a minimum, encouraging them to be aware of their stance while skiing and answering questions.

The results: 1) the disruptive student became engaged, taking the Grrrrrr out of the experience, 2) each student had a more cognitive experience about a simple traverse, and 3) it provided us with another class management tool. In the end, they better understood how a poorly accomplished traverse reflected a lack of alignment skills, which affected their free skiing.

Example 2: If GRR worked in a large clinic, why not in a class situation? My classes range from skiing easy blues to greens on one day to skiing the mountain on bumps and off-piste the next. My approach has been the same in applying GRR. I start each lesson with a goal and skill for students to try and accomplish. This skill may be taught throughout several lessons, but I break down the skill into bite size chunks, so we can concentrate on a specific body part or movement, which the students can easily observe.

At first, I demonstrate and explain, like we all do, using the “I do” stage of GRR. Then, I pair the students up, switching partners throughout the lesson, moving into the “We do together” stage. If it’s an odd number, I even pair one of the students with me. I become one of them when reporting observations. I use myself as the example of what I expect them to be observing. I instruct each set of partners to watch each other, reporting back what they observe, sharing those observations with the class. That way, I can make corrections as necessary. As they start to work more independently in the “You do together” stage, I invite the class to chime in to help with the corrections. I try to be more the observer. At first they were tentative. But after several attempts, I was blown away by what students observed and understood. I was amazed how quickly pupils started to understand the cause and effect of body movements to ski performance. It was just so cool! Normally, this level of understanding has been owned by the top performers in the class. Now, it was everyone in the class, and I knew to what level they owned the knowledge.

The other advantage is that all the students become engaged in the process. They have to pay attention, to understand, in order to teach another person. Students want to live up to expectations, and I set those expectations by defining what to observe and their responsibility to their partner. All I can say is they have responded to this approach. Remember the skepticism about utilizing such a model I discussed previously in this article? Professional vs. peer group input during a class? To confirm that GRR was working to their benefit, I asked my classes if they’d rather me just teach, not have them help each other, or continue having them help teach each other? I received a resounding affirmation of preference: being included in the teaching/learning process made the class more fun. They really liked

the GRR format.

I am wondering if anyone else has been trying GRR in their classes or clinics. If not, I urge you to try it. To me, this tool has brought more focus to each lesson and understanding from the pupil. GRR has also permitted me more time to check for understanding on an individual level, being able to customize the lesson for each pupil. Bottom line, I’m sold. It has been a great tool for me and taken some of the Grrrrrrr out of instructing, especially when dealing with larger groups. Thank you Linda for bringing this model to our attention. It’s a great tool.

Want to learn more about the Gradual Release Model?

Fisher and Frey Books and Publications

Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A Framework for the Gradual Release of Responsibility at Amazon.com

[divider top=”1″] David Berkey is a Level III Alpine, Level I Snowboard Instructor and TD for Olympic Ski School, at Stevens Pass, Wa. Email: david@scubaskier.com

David Berkey is a Level III Alpine, Level I Snowboard Instructor and TD for Olympic Ski School, at Stevens Pass, Wa. Email: david@scubaskier.com