today’s special: turn transitions

by Kate Morrell photos by Ron LeMaster

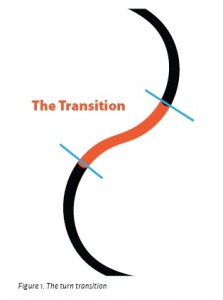

This article is essentially about turn transitions, and specifically how they relate to making carved turns on groomed terrain. As you may know, the turn transition is that portion of skiing that is from the exit of one turn, to the beginning of the next (see Fig 1). I like to think of turn transitions as the main course when it comes to cooking up a well carved turn and want to share a few important ingredients that all of us as ski professionals need to be able to apply and comprehend when cooking up a good transition.

This article is essentially about turn transitions, and specifically how they relate to making carved turns on groomed terrain. As you may know, the turn transition is that portion of skiing that is from the exit of one turn, to the beginning of the next (see Fig 1). I like to think of turn transitions as the main course when it comes to cooking up a well carved turn and want to share a few important ingredients that all of us as ski professionals need to be able to apply and comprehend when cooking up a good transition.

These ingredients are early pressure, moving through a balanced athletic position, and maintaining cuff pressure to both cuffs. This is not something new, or exciting, or a fad concept that will go away over time but is something that makes up the most critical part of the turn. Skiing well in the transition makes the rest of the turn pretty easy which is why the best ski racers in the world fight to be good at it and spend the better part of their careers working on it.

Ingredient 1: Early Pressure

The transition is where a skier establishes early pressure to the new turning ski. The earlier that pressure can be established, the higher up in the turn we can begin to carve the ski to the fall line. Yes, for sure, 100%, believe me that establishing early pressure is what we want to do when carving turns. The more pressure we can take care of before the fall line, the less pressure we have to deal with after the fall line. We want to minimize pressure as much as possible after the fall line because that is where the pressure is the greatest.

Excessive pressure after the fall line is one of the major reasons turns break down and flow from turn to turn is disrupted. By “turns breaking down” I mean skidding, losing the downhill edge, bracing against the outside ski, holding onto the turn too long for speed control, traversing, ski chatter, etc. – the list goes on. In effect, excessive pressure after the fall line hinders the ability to flow smoothly into the next turn.

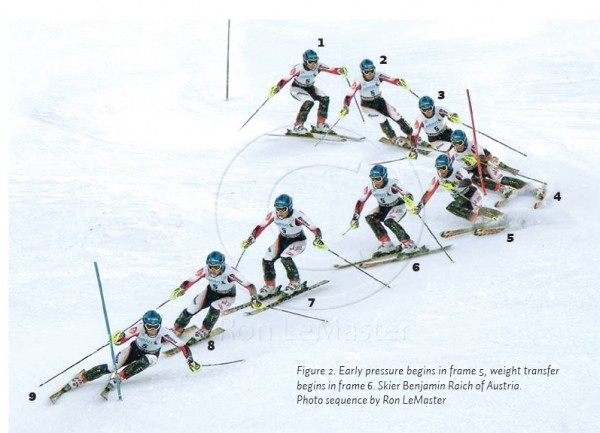

To establish early pressure, we first need to be “thinking” early pressure as we are exiting the turn. (Fig. 2: Slalom (SL), frame 5 and Fig. 3: Giant Slalom (GS), frame 11). With the knees and ankles flexed, feel for the uphill edge of the new turning ski and begin to transfer weight to it (Fig. 2: SL, frame 6 and Fig. 3: GS, frame 12). Continue pressuring the new uphill edge as the center of mass moves forward along the path of the ski.

Ingredient 2: Balanced Athletic Position

Time out! It’s already too hot in Kate’s kitchen. I can feel the resistance and panic from some of you already regarding the term “balanced athletic position.” Let me get this out of the way so you all can read freely. Yes, of course we want to be balanced and athletic through the entire turn, and no, this is not suggesting any sort of static skiing. This balanced athletic position is a “checkpoint” in the transition to look for in other’s skiing and strive for in our own. OK, now you may continue reading about a balanced athletic position as it relates to turn transition.

As our skis flatten out and we change edges, we must be able to move through a balanced athletic position (Fig.2: SL, frame 1 and between frames 6 & 7 and Fig.3: GS, frame 6 and between Frames 13 & 14). How we change edges is for another time but we should all agree to some degree that the knees and ankles are rolled and the center of mass moves forward along the path of the skis crossing over in the direction of the new turn.

This balanced athletic position has the center of mass over the feet with the ankles flexed. The angle of the spine matches the shin angles as we strive to keep the hands out front helping to maintain balance. It is only from this balanced athletic position that we can react well to the next turn. I can carve, steer, pivot, whatever. A balanced athletic stance is best seen in Fig.2: SL, frame 1 and in Fig. 3, GS, frame 6.

Ingredient 3: Cuff Pressure on Both Cuffs

This is another critical ingredient and you need to pay close attention. Maintain cuff pressure on both cuffs while changing edges and extending into the new turn (Fig.2: SL frame 7 and Fig.3: GS, frame 14). As we change edges, having both cuffs pressured does not mean that the feet are weighted equally. With our center of mass continuing forward along the length of the ski, the new turning ski (uphill ski) becomes weighted and cuff pressure to that ski is due to that weight transfer. Cuff pressure to the new inside foot is created mostly by actively flexing the ankle and resisting early ski lead (Fig.2: SL, frame 7).

If you stand on one foot, bend the ankle of the lifted foot and pull it back an inch or so you’re in the ball park of getting the feeling. This is very important because if we transfer weight to the new turning ski and relax our inside ankle without bending it and keeping it back, the inside foot moves forward causing the inside half of our body to slide forward much too early in the turn. When the inside half of the body moves forward too early, the result is skiing in the back seat and being too far inside. Back and inside is a difficult position to recover from and keeps us from being able to move smoothly into the next transition.

Said another way, when we cross over our feet we must actively bend our new inside ankle. To accomplish this, it helps to actively pull back the inside foot and lift the inside hip thus helping to maintain proper alignment and a strong inside half (Fig.2: SL, frames 7 & 8 and Fig.3: GS, frames 14 & 15).

Those are the only ingredients you get today but there are more I am excited to share later. What I’ve done here is give some tips that will aid in a strong transition and with the photo montages we have some checkpoints to look for when clinicing, teaching, watching video, etc. This all happens incredibly fast in real time and these checkpoint body positions should not hinder fluid movements in our skiing. What I’m trying to say is that I don’t want you skiing across the hill frozen on your uphill edge waiting to turn or frozen in the athletic position in the transition. I do want you to start familiarizing yourselves with these concepts and to start incorporating them into your own skiing, clinic, and lesson scenarios.

One more thing and then we can chill. As I mentioned, the transition happens incredibly fast and you will not always be able to identify these key components even in the best skiers so don’t get overly critical if you don’t see it happening in every turn in your skiing or the groups you are working with. Pressuring the uphill edge before the skis flatten will not always happen. Especially in slalom and giant slalom. Things are happening too fast and there isn’t always time.

Benjamin Raich of Austria (photo montage skier) has Olympic gold medals in the giant slalom and slalom, has won 35 World Cup races and has been on the podium 85 times. He is truly one of the best and he is able to demonstrate these transitions nicely for us in GS and slalom. He is truly the man.

The point is that having the ability to focus on these ingredients in longer, slower turns gives us an awareness of what is ideally happening between turns and position checkpoints to look for and move through in our own skiing.

I look forward to cooking this up on the hill with you and adding more ingredients in the future. I encourage you to shoot me an email for further discussion or questions this might raise. Thanks for your time in reading this. I hope you liked it!

[connections_list id=13 template_name=”div_staff_bio”]Editor’s Note: Special thanks goes to Ron LeMaster for use of the photo montages. Ron has spent more than 30 years as a ski instructor and race coach. He is a technical advisor to the US Ski Team and the Vail Ski School and has contributed to PSIA educational materials. His latest book Ultimate Skiing is a “must have” for your skiing library. See more montage images at www.ronlemaster.com.

To purchase a copy of Ultimate Skiing contact the PSIA-NW office. For this and additional titles just call the office or log onto the website and download a Bookstore Order form and fax it in. Your PSIA-NW bookstore purchase directly supports your Northwest Division.

4 thoughts on “Cooking with Kate”

Thanks Kate. I have been focusing on accurate weight transfer lately. It really has been helping me work on and maintain the other two ingredients in your recipe, though I still allow them to break down in more challenging situations. Your article is helping. I like the simplicity of in terms of things to “do”. I wish it were as simple for me to execute them all the time. Take care!

Easy to understand and informative article.

I’ve been working on resisting early tip lead in my own skiing lately and this helps to clarify concepts.

Thanks!

Thanks Kate. This is a great article. Thank you for being so definitive!

Kate – I just finished a TD training with some awesome people. One of your points about getting an early ski lead causing the body to be back and inside became a topic of conversation. Then I found myself guilty of it on long radius turns. Wow! What a wake up call. Now I concentrate on that inside ankle being back further, so I’m not recovering for the next turn. I have found that as equipment changes, so does stance, since the equipment does so much of the work. Yet, it’s still the same, getting the tip of the equipment to create deflection through cuff pressure. The old axiom of “get forward” is not totally accurate any longer. It’s use the equipment, boots and skis, to create the necessary pressures required to generate turns. Meanwhile, stay athletically balanced over the feet, not letting them get ahead of you. Forget the “pretty boy” stuff. Get those legs part, get loose and rip it! Love your recipe.