by Tara Seymour photos by Jeff Seymour

The trip began like any other trip to Europe, with a lot of jet lag and anticipation for the up coming adventure. We were anxious to get on our skis and out of the crowded town of Zermatt, Switzerland. The Matterhorn looming in the view of every street reminded us we were definitely in the Swiss Alps. The weather was nice and we were staying two days in town to acclimatize to the mile-high elevation. We spent the first day getting to know our touring group consisting of three mountaineering guides and four clients: two friends, my husband and me. We were all very excited and determined to make this trip amazing and safe!

The Haute Route a.k.a. the “high route” has been a huge part of the history of skiing and mountaineering in the Alps. This was something that I had personally wanted to ski for over ten years and now I was standing in the shadows of the Matterhorn with excitement that caused my stomach to swirl. After much cheese fondue and poor Swiss wine we made our way to bed.

The first day of acclimation included skiing the huge and endless terrain of Zermatt with its many ski areas. With my PSIA Level III Certification and ISSA international membership, I was compensated at nearly all resorts. The day was not spent free skiing, but rather assessing each other’s skiing skills in a variety of diverse conditions, steeps, etc. Time was spent starting and stopping in certain places and very specific distances apart in preparation for the high country. All of this was conducted while wearing our outfitted 25+ pound backpacks. Part of the day was also spent reviewing usage of our avalanche beckons and transceivers. Knowing the abilities of your peers can be a life or death situation in climbing and backcountry skiing. Our three American guides were very helpful, qualified and knowledgeable in all the safety precautions necessary when navigating these mountains. I felt very safe in their hands.

Typically this route can be completed in 8-10 days. Our first day on route was not perfect; it was very windy and sub-zero all day but was both challenging and rewarding. It was necessary to use crampons to make the ascent to the first hut, and with day one finally over, I had already been pushed out of my comfort zone on more than one instance.

Those not familiar with the Haute Route, this ski-touring trip consisted of skiing up and down mountains for long portions of the day, in various conditions from wind pack and breakable crust to the “light and fluffy” we were hoping for. Some days high winds would attack in gusts while other times would remain at a steady speed of 20 m.p.h. or more suited to windsurfing than ski touring. Regardless of the snow conditions all the days were very cold and long with the huts as a physical and mental end goal. The final approach to the Bertol hut was “totally insane” one of which we had to climb a near-vertical craggy face to get to the hut that was perched on the edge of a precipice. The final relief was closing the hut door as if being inside would somehow render our precarious locale harmless. The huts were usually warmer inside than outside and typically had some sort of edible food and wine as dinner for the weary. The dinner conversation always revolved around the incredible mountain landscape and the phenomenal skiing.

Just as we knew that the sun would rise, snow fell frequently accumulating overnight. On the morning of the fifth day of our adventure across the Alps, we awoke to more than 16 inches of snow that had fallen during the night. The wind was gusting up to 60 m.p.h. Typically we would start our day out around 7 am, but on this day we waited and debated. The guides poured over maps and conversed among themselves. Finally at 10 am the weather cleared a bit, the sun peeked out, and although it was still very windy, at least we were off to the next hut.

The wind was truly an issue. We were cold and the snow was being blown all around, creating poor visibility. We considered turning back, but we all decided to keep moving forward. The thought of turning around felt like failure to us. The guides led us up the first col between two peaks then across a large glacier. As we approached the next col, the winds increased as they funneled through the gap. The guides requested we remove our skis from our boots and carry them part way over the col. At this point we could see nothing due to snow being blown up the slope. Pitch, length and terrain were all a mystery to us.

The guides dug a quick pit to check the snow conditions. In an effort to get some relief from the wind, the guides built a snow anchor from skis and rope. We were then lowered down about 100 feet to a rock outcropping. We were hoping to lower out of the wind a bit more and get down far enough to see what the slope was going to be like for our descent. The four clients went first with one guide at the bottom, helping us off the anchor, and the other two at the top getting us hooked in.

With all four of us standing on a rock island in the middle of the huge valley, we heard the most horrifying sound you would ever want to hear. So loud it silenced the wind, “CRACK!” The sound of an avalanche!

The sound was terrifying for only a moment. Then blown off the rock island by hurricane force wind, flying through the air, hitting the ground hard, I was really scared. Flying again in the air with snow engulfing me, the first thought any parent would have, was of my kids. How could I possibly leave them orphans? I did not know if my husband was caught in this nightmare as well, or maybe he was fine. Finally the turbulence was slowing after what seemed like an eternity that inevitably lasted less than a minute all together. I felt the power of the snow settle around me and I could move nothing. Panic now overcame fear.

Getting my wits together I could see light about two feet up, or so it seemed. I tried to move, but could not. I tried to conserve breath, slow down, not panic. Could I move something? Yes, my left wrist! It was partially free. I started using my fingers to dig towards my face. I had about three inches of air around my face and knew that was not going to last long. I kept digging quickly making progress slowly. I was under about 4 minutes when I heard muffled noises. I tried to scream, but snow fell in my mouth choking me. Relax. I knew that they had found me. My beacon had worked.

An airway was dug out of the snow and I knew that I was alive, and my children would still have a mother. I did not feel any major pain, but knew that the adrenaline had kicked in. It took ten minutes to carefully dig me out. My rescuer and good friend told me that my husband was okay and was being dug out, but that the other two were still not found.

Freed from my would be tomb, the ordeal had really just begun. There were two more people buried somewhere. I joined the search. We found the next person 200 feet below me with severe injuries and needing real help. The last person was found another 200 feet down slope and had been buried for six minutes or more. Again we had a major injury and needed help. With all accounted for the lead guide, whose skis wear lost somewhere in the avalanche debris, was able to piece together enough ski equipment from the scattered and lost gear. He took off immediately for the next hut on our destination about 10 km away on his make shift touring setup. Our lost gear was the least of our concerns as we prepared temporary shelter for the injured.

Then we waited. It was three hours before we heard the Air Zermatt choppers. When they arrived it was far too windy for them to land near us, so the Swiss guides aboard the helicopters skied up to us and extracted the injured to the landing zone where the choppers could lift them out safely. The Swiss Mountain Guides were truly amazing to see at work.

The weather had lifted enough to visually approximate the ordeal. We slid down more than 1,000 vertical feet, over two rocky cliffs and lived to tell about it, due to the swift actions of our team in locating the buried using transceivers, and successfully digging them out in time to avoid suffocation. Not everyone is as lucky.

Avalanche Safety Basics

If caught and buried in an avalanche you are more likely to be found if you wear a beacon. A beacon is only useful if the members in your party know how to locate it using a transceiver. You should also always carry a shovel, probes and in most cases be wearing a harness. When traveling in the backcountry, the side-country (special areas that are part of a resort’s permit area but may or may not be well avalanche controlled), or even in-bounds at your resort, any open slope between 30° and 45° may be at risk of sliding. More Difficult (Blue Square) terrain has a slope of typically 20° to 30° while Most Difficult (black diamond) terrain has a slope of typically 30° to 40° and Expert Only (Double Black diamond) terrain is typically 40° or more.

Even small avalanches are a serious danger to life, even with properly trained and equipped companions who avoid the avalanche. Between 55 and 65 percent of victims buried in the open are killed, and only 80 percent of the victims remaining on the surface survive.

Research carried out in Italy based on 422 buried skiers indicates how the chances of survival drops very rapidly from 92% within 15 minutes to only 30% after 35 minutes where victims die of suffocation to near zero after two hours where victims die of injuries or Hypothermia.

Historically, the chances of survival were estimated at 85% within 15 minutes, 50% within 30 minutes, 20% within one hour.

Avalanche Info

Avalanche starting zones generally occur on slopes between 30 and 60 degrees. They can run, and even accelerate, at pitches between 15 and 30 degrees especially when confined, such as the terrain in a narrow canyon. When the slopes hit 15 degrees or less the avalanche will generally decelerate to a stop, leaving huge amounts of debris in the deposition zone.

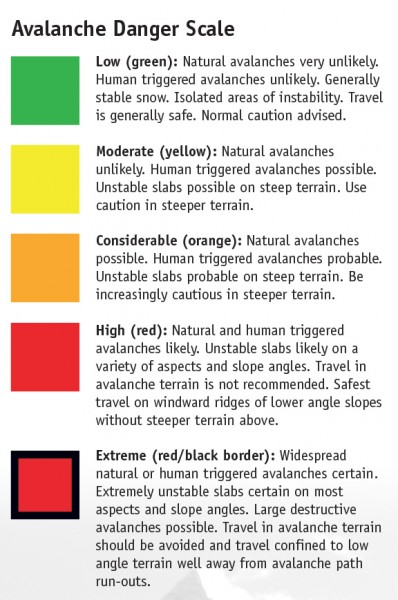

In terms of size, avalanches are measured on “R = Relative size to path” and “D = Destructive Force” scales from 1 to 5, 5 being the largest and most destructive. The avalanche we were caught in was classified as R4/D5. In the United States and Canada and the following avalanche danger scale is used. Descriptors vary depending on country.

In Summary

I am sharing this story to inspire my fellow members of PSIA to inspire you to get backcountry and avalanche education, both for you and your students. It is important that our members become more aware of the dangers of avalanches in the backcountry, side-country and even within our own ski area boundaries, as many snowsports enthusiasts are seeking out the backcountry experience. I love to ski the backcountry still, and take all the precaution when doing so.

Most of us ski and ride at resorts that control the dangers of the avalanches; however avalanche control does not completely remove the danger of avalanche, it just reduces it. It is my belief that if you work in the snowsports industry you should attain your Level 1 Avalanche training. Some ski areas in the Northwest and beyond require instructors to wear beacons, while most general public don’t even know what they are.

As members of the snowsports education profession, I contend, it is our responsibility to know as much about basic avalanche safety as it is to teaching a basic parallel turn. •

Avalanche Related Info & Links:

Alaska: www.alaskaavalanche.com

Idaho (northern) : www.thesnowschool.com

Montana (western): www.missoulaavalanche.org

Northwest Weather & Avalanche Center: www.nwac.us

Oregon: www.i-world.net/oma

Oregon (central): www.coavalanche.org

Washington(central):www.mountainmadness.com

Washington (western): www.mountainsavvy.com

Editor’s Note: There is a well photographed and documented naturally occurring avalanche that happened during the Winter 2009/2010 Season at Mt. Hood Meadows. It was a very large avalanche (R4, D4) that started outside the permit area, however traveled more than 2.5 miles and nearly 6,000’ vertical feet well into the resort area stopping 200 yards from the bottom terminal of the Heather Canyon chairlift. Go to this link for more information: www.skihood.com/Community-and-News/Meadows-Blog/Posts/2010/01/Anatomy-of-an-Avalanche

[connections_list id=39 template_name=”div_staff_bio”]

One thought on “Avalanche: Buried Alive but Lived to Tell”

Great Article Tara! Glad you are here to tell the story, I will be looking to get more education on avalanche safety for sure, was witness to the aftermath of a major slide in Heather Canyon that came from out of area and nearly made it to the Base of the Heather Canyon lift as noted by the editor, had been skiing in the area not more than 8 hrs prior to the slide. Makes you think….