Develop Strength & Balance for Performance Riding

Develop Strength & Balance for Performance Riding

by Chris Hargrave, originally published in the Winter 2009 Issue of the NW Snowsports Instructor

One of the greatest challenges in snowboarding is the ability to bend the nose and tail at will in dynamic sliding environments. Skillful controlled riding should be supported by the ability to bend the nose, center, and tail of the board to varying degrees as desired by the rider and demanded by terrain and speed. As riders grow in experience all kinds of compensatory habits are created to cover up inabilities or weaknesses in the fore/aft or foot-to-foot range of motion.

While watching riders in tough terrain full of transitions and undulations it becomes clear that reactive and recovery riding is a dominant trend. Working toward proactive and accurate management of the nose, center, and tail flex of the board through the independent action of the joints of the legs is critical to unlocking new lines and greater control.

Think about how many times you’ve been loaded up and tossed in the moguls, kicked toward your tail off a quick transitioned jump, felt that skid in a carved turn, pivoted more than you might like in your short turns, or felt awkward trying to ollie at speed. Each of these symptoms can be caused by inaccurate application or control of the foot-to-foot range.

Why is it so hard to bend and pressure the nose when sliding? No time spent developing strength and balance over the movements that bend and press the nose (see figure 1).

Why do riders spend so much time battling the tail load? Progressing in riding without developing strength in fore movements will lead to fear and apprehension as the terrain gets more intense and will cause movement restrictions.

What is the key to working the board through and from the center? Strengthening and developing the entire rage of motion through the extremes to create freedom and understanding of what the moves feel like and how to control them.

Riders spend hours in clinics trying to analyze these challenges in riding and try tweaking a little thing here or there. If the range has not been developed then riders are only ready, from a strength and muscle memory perspective, to achieve small bits of success and slightly better feelings. Tweaking riding problems in dynamic sliding environments without the foundations to support the changes can often be an unsuccessful approach to treating the symptoms.

Treating the cause is the answer and it’s so simple that it’s easy to miss. Riders must do the hard work to build a foundation of support to enable strong movements in dynamic terrain settings. How much time do riders spend focused on building their balance, strength, agility, and stamina in the foot-to-foot range? Answering this question is easy just take moment to watch the overall picture and style of a few riders on any mountain. It’s common to see choppy-jerky-awkward movements in riders who haven’t built up the range and smooth-fluid-sweet style in those who have.

When most riders start out they are focused on going, shredding, killing it, having fun freely cruising and flowing turns top to bottom. What that really means is we learn to turn first at any cost then build our ability to create accurate-smooth-styley movements while turning much later in the process. Once a rider is given the keys to the mountain (skidding, traversing, and linked turns) they are off exploring and that’s a great thing. However when riders truly want to progress sometimes the best thing to do is go back to basics and build awareness and control of movements through all their ranges of motion.

Building strength in the ranges of motion and very specifically in the foot-to-foot range is so critical to dynamic growth. So often riders come to exams with a very limited ability to work the foot-to-foot range and they struggle with many of the key skills and demos that we look for. Dynamic skidded turns, bumps, ollies, pipe, switch, steeps almost every demo truly requires a skilled understanding of the foot-to-foot range. Students struggle with pressuring the nose of the board. They must think that instructors only know these words, “Put more weight over the front foot!”

Static or limited foot-to-foot movements really start to show when riders get into tough terrain environments. Often falling toward the tail when hitting a jump or rail, kicking the tail of the board around in a violent wafting manner in turning, getting tossed in the moguls, or struggling to make that first toe side turn. Snowboards are designed to load and release energy so riders must spend time building the foot-to-foot range or they’ll get bucked by the changes in terrain!

Challenging terrain environments demand specific and skillfully timed pressure control movements of the lead and rear leg both independent (nose and tail pressure) and simultaneously (center pressure). As important as it is to know how to make the movements, riders need to know how it feels when the board reacts to the movements. From bending the nose and tail so far that the board pops out and the rider falls to controlling balance up to a high blocked position to a gentle pressed position to a slightly loaded feel to a center pressure feel. Each stage of development unlocks new understandings of how to balance, manipulate, and recover from the de-cambering and rebounding or popping action of the board.

One of the best ways to accomplish this type of strengthening and growth starts with static foot-to-foot work. Riders then progress to low speed/intensity work, later to higher speeds and more dynamic environments. The framework for growth in this article will deal with four static drills to introduce riders to the potential flex of the board and their ability to create and control the action.

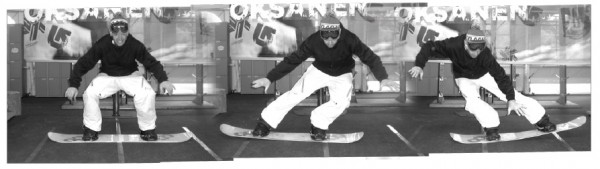

The Nose and Tail Press (see Fig. 2)

Static: Start in a low stance. Slide the board under the body by extending of one leg and flexing the other. Keep the body upright and tip shoulders toward the extended leg. Sink lower into your stance to create a stronger pressed position. Tip the knee of the pressing leg toward the pressing end of the board. Seek feel pressure over the outside edge of the pressing foot. Sit lower moving the core toward the pressing foot and the board will begin to bend. This skill will help riders understand balance and recovery control with independent leg action over the nose and tail.

Low intensity sliding: Take this move to the most gentle slope where speed control is not an issue. Start directly in the fall line in a low center stance. Practice sliding to the tail and nose and holding in the low seated stance. As strength is developed in the press work toward popping off the nose or tail and return to center as the press is released. Remember it’s never a lift, it’s always an extension of the lead leg and flexing of the rear leg. There should be no strain or stretch through the hip flexors.

Beyond: The next steps for this skill are to add speed and change the terrain aspect. Work them on moderate slopes. Work them while traversing across the hill. When traversing the tail or nose press point will shift to the up hill edge and will turn into a skidded feeling.

The Nose & Tail Bleed or Tripod (see Fig. 3)

Static: Rotate the shoulders and face the tail of the board. Slide the board under the body. Focus on a straight lead leg. Bend at the waist and bow toward the tail of the board. Place both hands on the ground. Extend the rear leg completely to force the tail to pop out. The nose of the board should point straight up at the sky. Balance on the tail and both hands in a 3 point stance. After holding the position for a few seconds tip the board toward the toe-side edge and set it down gently. Push up and try the other end of the board. Work with this until the tail or nose easily pops with enough energy to get to come up off the ground before it stabs into the snow. Try to feel the board bend and load extremely hard as the bent leg straightens. This skill will help riders understand the complete foot-to-foot range and the limitations/load points of their board raising awareness of just how far they can really bend it.

Low intensity sliding: On a gentle slope try starting switch and regular sliding directly in the fall line. For the bleeding version (sliding) we always tip to the uphill end of the board. Once in the tripod position be prepared to allow the hands to drag and the board to continue sliding down the fall line. To get back up bend the pressing leg to load the sliding end of the board. Use a strong push with the arms to upright.

Beyond: Add speed and pitch to create a greater challenge. This trick leads right into hand plants.

The Nose & Tail Check and Block (see Fig. 4)

The tail check is all about a strong focus on pressing the board with a completely extended rear leg and a bent front leg. It’s easy to get a feel for this on a balance board or skate board. On a snowboard, start in a low stance loaded slightly over the nose. Rock/shift the core over the center of the board toward the tail. Extend both legs like jumping way out over the tail. Quickly start to bend the lead leg and tip the lower half of the lead leg toward the nose of the board. Stay focused on fully extending the rear leg. Work toward feeling like the lead leg and the nose of the board are getting really close together. Feel lots of pressure toward the outside cuff of the lead boot. Hold the extension as much as possible until feeling the tail bend, with enough force that it creates some bounce. The first few times riders will likely get pulled right down to a flat base in falling action from the tail. Keep at it until able to stand with a fully extended rear leg and hold a full press for a few seconds. The tail check is the first step to learning a good tail block. The block is a stronger version of the check. Jump harder into the tail check position and bend that lead leg so much that it’s possible to reach the nose of the board with the lead hand and later both hands for a strong grip. This skill will help riders truly feel and control the limits of the flex of the nose and tail with a complete separation of the legs in a static position.

Low intensity sliding: Find a gentle fall line transition like a small jump ramp or even better the bottom of a quarter pipe. Start out very close to the bottom of the transition to keep the speed slow and avoid generating enough speed to go over the top. Start with the tail check and work it into a full-on grabbed block. Drop in at the transition in a low stance loaded slightly to the uphill foot. Ride up the transition and time the rock and extension to the up-transition foot when a little deceleration is felt. To get up into the press requires a strong active move and it will feel like trying to jump to the top of the transition to make it work. Once the check and/or grabbed block is held, bounce a little on the board and pop back into the transition to slide away.

Beyond: Next steps with these include taking them to different types of transitions and working them from traverses. The last couple wall hits in the half pipe are a great place or side walls along traverse tracks. Remember to work toward a clean apex and feel some deceleration before attempting the trick.

The Ollie and Nollie (see Fig. 5)

Start in a low stance. Tip the lower half of the lead leg toward the nose of the board. Slide the board under the body to load the tail (like the tail press). Try to feel the outside edge of the rear foot load up with pressure. Make sure the rear knee is tipped toward the tail (this will help lever the tail harder). Extend the rear leg. Keep the line of the shoulders slightly tipped toward the nose of the board. Release the tail of the board by retracting the legs and pulling the knees up toward chest. In the air the board will move back to center under the core. Extend legs and stomp board down. Absorb impact by bending ankles knees and hips. This skill will help riders feel full and blended pressuring and flexing action of the board, create independent leg movements of the front and rear legs, and create a stronger sense of upper and lower body separation.

Low intensity sliding: Head to the gentle slope. Practice both the ollie and nollie directly in the fall line. If the speed is making this hard the slope is too steep. As the ollie and nollie feel more comfortable see how many can be done in a sequence. Go for 3-5 and work up.

Beyond: Performing this trick on steeper slopes, across fall line, and over or off of transitions and little bumps is the next step. In general it’s time to put this trick to the test in all sorts of scenarios. The sequence of the ollie is so similar to the fluid independent mechanics of turning. This movement pattern will help control trajectory and set up or anticipate pressure changes. The keys to the kingdom reside in this movement, oh yeah baby!

Each of these drills will give the rider greater balance over the nose and tail of the board and independent strength from one leg to the other. The ultimate goal is to have so much strength in a static setting with each leg that the rider can then put these drills into action while sliding. Once the extremes of the range are under control the rider will have the strength and ability to start working toward smaller and more subtle adjustments in high level riding. Sometimes the best lessons are learned by straying far from the path only to learn that one must return to it grasshopper.

Strengthening this range of motion is the path to fully enjoying all that the board can do, greater balance and ability to maneuver, stomped tricks in the pipe and park, and access to unique and often overlooked lines on the mountain. Riders and instructors should spend a lifetime developing and mastering control over the flex of the snowboard. So many fun, playful, and creative tricks stem from this range. So many high level riding skills and tactics depend on accurate control of this range. For any rider working toward better snowboarding, better teaching progressions, and success in exams this season is a great time to start milking this range for all it’s worth. Remember almost every maneuver and type of terrain demands bending action from the board. Riders can choose to bend their board or the mountain will surely bend it for them and when they least expect or want it.

A final thought…

You’re shredding it up at your favorite mountain (Stevens Pass). All the easy pow has been shredded, destroyed, pummeled, and annihilated … argh! The last stash of pow is trapped between a mogul field, a nasty scraped off tree run, and a gnarly chewed up chute. To enter the field you have to gap off a tight little transition, that was formed up on a downed tree, over a little pile of rocks. The only question you have to answer is how skilled are you at working the board from nose to tail and working the board through all those tight spots. Put time and energy every day into strengthening this range and you and your students will, I promise, taste the sweet glory that is the secret stash shred. The local heroes will only be bummed for a little while that new shrelpers have learned how to access their world, then they’ll be cheering and leading the way to new terrain and new tricks all over the hill. At least, that’s the dream…

[connections_list id=48 template_name=”div_staff_bio”]